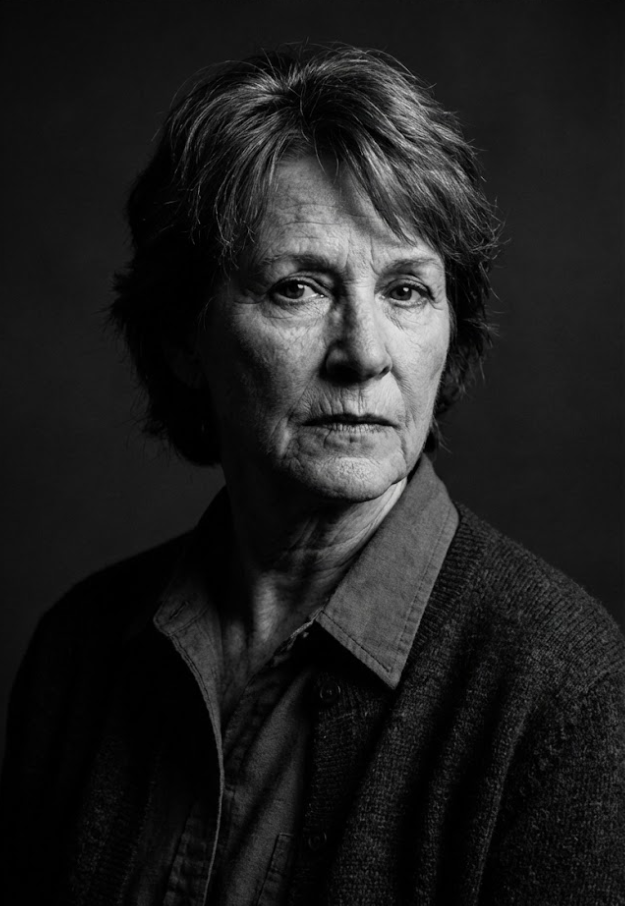

Early Life

Margaret Ann Sullivan was born on a Tuesday in late autumn, 1928, in the high, thin air of Missoula, Montana. To understand Margaret is to understand the landscape of her beginnings—a world defined by the jagged authority of the Rockies and the relentless, scouring wind of the Bitterroot Valley. She was the daughter of David Michael Sullivan and Mary Elizabeth O'Shea, second-generation Irish immigrants who carried with them the twin burdens of the Great Depression and an unshakable belief in the dignity of the written word.

Her father was a clerk for the Northern Pacific Railway, and her mother was a woman who kept a volume of Yeats hidden beneath the recipe books in the kitchen. In the Sullivan household, literacy was not merely a skill; it was a form of prayer, a way of asserting presence in a vast and often indifferent geography. Margaret, the eldest of four daughters, grew up in a house where the sound of the kettle was often accompanied by the rhythmic cadence of oral recitation. It was here, amidst the scent of coal smoke and old paper, that she first learned that language was a system of gears and levers—a mechanism that, if properly maintained, could move the world.

The Education of a Teacher

Margaret's path was marked by a quiet, determined clarity. While the girls of her generation were often encouraged toward the domestic arts, Margaret was drawn to the rigor of the humanities. She attended the University of Montana on a modest scholarship provided by a local Catholic parish, studying English Literature and Philosophy.

Those years in Missoula in the late 1940s were transformative. She walked the campus under the shadow of Mount Sentinel, carrying the works of Thomas Aquinas and Virginia Woolf. She was a student of "coherence"—a word that would become the cornerstone of her personal philosophy. She believed that a sentence was a structural feat as impressive as any bridge, and that a well-placed comma was as essential as a keystone.

Upon graduation in 1950, she moved west to Spokane, Washington, seeking a position in the burgeoning public school system. It was a time of postwar optimism, a period when the Pacific Northwest was beginning to expand its industrial and intellectual borders. She accepted a post at Sacajawea Middle School, a brick-and-mortar institution that sat like a quiet fortress amidst the pine-covered foothills. It was in Spokane, during a rain-slicked evening at a social hall for railroad employees, that she met Robert James Murphy Sr.

The Mechanic and the Muse

Daniel Murphy was a man of metal and silence. A railroad mechanic for the Burlington Northern line, he lived in a world of tolerances and torque. He possessed a stutter that made public speech an ordeal, but his hands were capable of a terrifying precision. Margaret was captivated by him—not for what he said, but for the way he listened. She saw in his mechanical aptitude a different kind of grammar, a silent poetry of function and form.

They married in 1951. The union was, to outside observers, an unlikely pairing: the literature teacher with the polished vocabulary and the grease-stained mechanic who spoke in fragments. Yet, within the walls of their small home east of the city, they built a shared language of mutual respect. Margaret never corrected Robert's speech; she simply provided the space for his silence to be heard.

In the decade that followed, they had three children: Michael Patrick in 1950, James Robert in 1953, and Catherine Marie in 1956. Margaret viewed motherhood not as a departure from her intellectual life, but as an extension of her classroom. Her children were her most important students, and the Murphy household became a laboratory for the integration of the mechanical and the lyrical.

The Liturgy of the Evening

The defining ritual of Margaret's life—and the one that would most profoundly shape her son James—was the evening reading. After the dishes were cleared and the Spokane winter pressed against the windows, Margaret would sit in the armchair beneath the yellow glow of a floor lamp. With her glasses reflecting the soft light, she would read aloud.

She did not read children's stories. Instead, she introduced her young family to the "mechanical poetry" of Ray Bradbury's The Martian Chronicles and the dusty, moral weight of John Steinbeck's The Grapes of Wrath. To Margaret, these authors were essential because they understood the intersection of human yearning and the physical world.

She would pause after a particularly resonant passage, looking at her children—Michael, restless and already dreaming of the sea; Catherine, watching her mother with an apprentice's eye; and James, who sat with the stillness of a statue. It was during these sessions that she taught them that "human stories and mechanical systems shared the same need—coherence." She showed them that a rocket launch was, in its essence, a narrative arc, and that a life lived without a sense of structure was a story that could not hold its own weight.

Teaching

For thirty years, Margaret taught seventh-grade literature at Sacajawea Middle School. She was known as a formidable but deeply fair instructor. In an era of shifting pedagogical trends, she remained a traditionalist regarding the "architecture of the sentence." She forced her students to diagram sentences on the chalkboard until they could see the skeleton of the thought beneath the skin of the words.

She had a particular affinity for the "difficult" students—the boys who, like her husband, had hands meant for engines but minds that felt trapped by the page. She would bring in technical manuals and ask them to find the verbs, showing them that even a schematic for a tractor was a form of literature.

Her colleagues remembered her for her "unflappable stillness." She walked the hallways with a straight-backed grace, usually carrying a stack of essays marked with her signature green ink. She didn't believe in the cruelty of red ink; green, she said, was the color of growth and revision. She taught her students that to edit one's work was an act of humility—a recognition that the first draft of the world is rarely the best one.

The Quiet Witness

As her children grew and departed, Margaret became a quiet witness to their trajectories. She watched Michael head North to the Bering Sea, his letters home filled with the harsh, monosyllabic reality of the fishing life. She saw Catherine step into the classroom, carrying forward the Sullivan legacy of teaching. And she watched James leave for Purdue and later NASA, moving from the geography of the pine hills to the geography of the stars.

When James worked on the Space Shuttle program, Margaret followed every launch with a professional's focus. To her, the Shuttle was not just a feat of engineering; it was a poem written in titanium and ceramic tile. When the Challenger disaster occurred in 1986, she did not call James immediately. She knew the silence he would be sitting in. Instead, she sent him a copy of Gerard Manley Hopkins' poetry, with a single line underlined: "And for all this, nature is never spent; There lives the dearest freshness deep down things."

Final Years

Daniel passed away in 1998, and the silence in the Spokane house deepened. Margaret met her widowhood with the same stoicism she had applied to everything else. She retired from teaching but remained a constant presence in the Spokane library system, volunteering to record audiobooks for the blind—her voice, aged but still rhythmic, carrying the stories of others into the dark.

She passed away in the winter of 2007, a few months shy of her 80th birthday. At her funeral, the small chapel in Spokane was filled not only with her family but with decades of former students—mechanics, nurses, engineers, and teachers—who had learned from her how to construct a life of coherence.

James would later establish the Robert J. and Margaret A. Murphy Engineering Scholarship, but the true legacy of Margaret Sullivan was not found in a fund or a plaque. It was found in the way her children viewed the world: as a place that could be understood through patience, precision, and the courage to look at the "hidden geography" of things.

She lies in the cemetery on the hill, overlooking the Spokane Valley. Below, the railroad tracks where her husband worked still gleam in the winter light, and the wind from Montana still carries the scent of pine and old paper—a final, coherent sentence in the long story of her life.