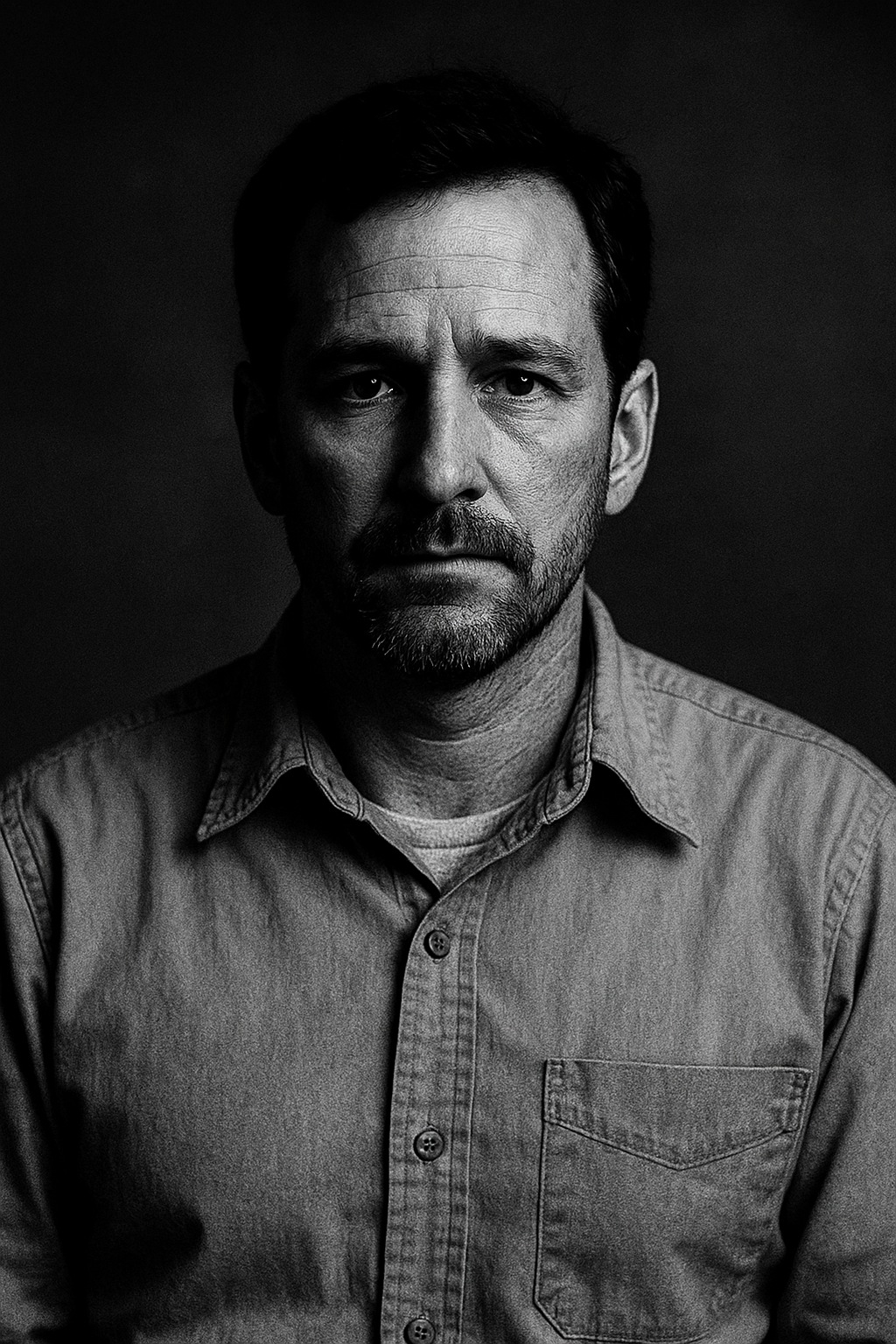

Early Life and Family

James Robert Murphy was born in the winter of 1953 in Spokane, Washington, to Robert James Murphy Sr. and Margaret Ann (Sullivan) Murphy. His childhood unfolded in the shadow of the pine-covered foothills east of the city, where snowmelt ran down into the Spokane River and summer light poured through the dust of half-paved streets.

Murphy's father, Daniel James Murphy Sr., was a railroad mechanic for the Burlington Northern line—a quiet man with grease-stained hands and a stutter he never quite conquered. He kept a workbench in the garage stacked with carburetors and broken clocks, a sanctuary where precision and patience were the only languages spoken. It was there, at seven, that James first took apart a transistor radio just to see its hidden geography.

His mother, Margaret Ann Sullivan, came from a family of Irish Catholic schoolteachers in Montana. She taught seventh-grade literature at Sacajawea Middle School and brought home the rhythms of language and story. In evenings, she read him Ray Bradbury and Steinbeck aloud; he would listen in silence, watching the reflection of her glasses in the lamplight and feeling that human stories and mechanical systems shared the same need—coherence.

James grew up with two siblings: an older brother, Michael Patrick Murphy (born 1950), who became a commercial fisherman in Alaska, and a younger sister, Catherine Marie Murphy (born 1956), who followed their mother into teaching and still lives in Spokane. The three Murphy children learned early the value of self-reliance—their father's long shifts at the rail yard and their mother's evening lesson planning meant they often fended for themselves, developing a tight bond forged in the quiet spaces of their childhood home.

Education and Early Career

After high school, Murphy left Spokane with a single suitcase and a scholarship to Purdue University, where he studied mechanical engineering. The Midwest struck him as boundless and melancholic, its flat fields echoing a kind of inward quiet. He excelled in thermodynamics and materials science but spent equal time in the campus observatory, tracing the orbits of Mars and Jupiter.

He graduated in 1975, then pursued a master's degree at the University of Colorado Boulder, drawn by both the mountains and the nascent frontier of American spaceflight. The mid-1970s were years of anxiety and ambition at NASA: the Apollo triumph was fading, and the Space Shuttle promised to make space routine—an idea both audacious and oddly domestic. Murphy was hired as a junior engineer at Rockwell International, which was then building the Shuttle's orbiter structure.

NASA and the Space Shuttle Program

Murphy joined NASA officially in 1981, the same year Columbia first launched. He was assigned to Kennedy Space Center as part of the propulsion integration team. His work was rarely glamorous—he spent long nights verifying the minutiae of hydraulic systems, documenting data that would never make it into press releases. Yet, to him, the Shuttle was a cathedral of human will: a structure built not of marble but of equations and faith.

Colleagues remembered his stillness in meetings, the way he would turn a pencil slowly between his fingers before speaking. He carried a small black notebook filled with his own sketches of valve assemblies and notes about his children's birthdays.

When Challenger was lost in 1986, Murphy was on-site. In later interviews, he would describe the silence afterward as "the sound of every engineer remembering that numbers have souls." He stayed on through the redesign years, contributing to the structural safety protocols that helped return the Shuttle to flight.

In 1993 he received the NASA Exceptional Achievement Medal, though he kept it in a desk drawer, saying it belonged to "the work, not the worker."

Personal Life

Murphy married Linda Marie Hartman, a biology graduate student, in 1981. They met at a coffee shop near Cocoa Beach—she was sketching marine algae; he was reading Clarke's Rendezvous with Rama. Their marriage was steady, marked by mutual curiosity rather than passion. She taught high school science, and together they raised two children near Titusville, Florida, in a small house whose backyard faced a strip of sky wide enough to see the launches.

Their daughter, Jennifer Lynn Murphy, was born in 1983 and became a software engineer in Seattle, drawn to systems thinking in a different medium. Their son, Daniel Robert Murphy, was born in 1986—the same year as the Challenger disaster—and grew up to become an emergency room physician in Orlando, carrying forward his father's quiet commitment to precision under pressure.

Murphy's brother Michael remained a distant but steady presence, sending postcards from Dutch Harbor and king crab from the Bering Sea each Christmas. His sister Catherine visited Florida twice a year, bringing news from Spokane and reminding James of their mother's evening readings—a ritual Catherine now performed with her own students.

Their father, Daniel, passed away in 1998 from lung disease; their mother Margaret followed in 2007. James returned to Spokane for both funerals, standing in the cemetery on the hill overlooking the valley where the railroad tracks still gleamed in the winter light.

He never learned to stop working. Even after retirement in 2011, Murphy rose before dawn to write in his journal or restore old pocket watches. Friends describe him as contemplative, prone to quoting Marcus Aurelius, and convinced that the most enduring form of progress was humility before the unknown.

In a rare interview he said, "I think space is not an escape from Earth—it's the echo of Earth's restlessness inside us."

Legacy

James Robert Murphy's career spanned the full arc of the Shuttle program—from the exuberant 1980s to its closing decade. Though his name never appeared in the headlines, his fingerprints remain on the schematics that made the orbiters reusable, and on the thousands of pages of handwritten notes that guided future engineers.

In retirement he has supported STEM programs for rural schools in Washington State, quietly funding scholarships in his parents' names—the Robert J. and Margaret A. Murphy Engineering Scholarship for students from working-class backgrounds. He remains a believer in the "mechanical poetry" of engineering—that to build something that leaves the ground is to honor both gravity and grace.