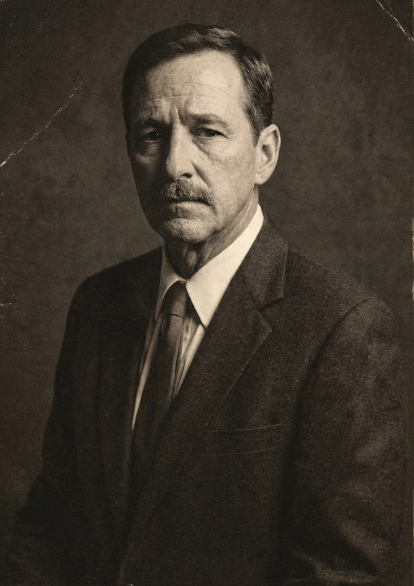

Early Life

David Michael Sullivan was born on August 14, 1898, in Tacoma, Washington, to James Patrick Sullivan and Martha Vance. His parents were immigrants from County Cork, Ireland, who settled in the Pacific Northwest during the industrial expansion of the late nineteenth century. David grew up in a household where economic stability was prioritized, and he began working part-time at the local rail yards while still in secondary school.

In 1917, following the United States' entry into World War I, David enlisted in the U.S. Navy. He served as a machinist’s mate, a role that required him to maintain and repair mechanical systems aboard transport ships in the Atlantic. This period established his professional foundation in technical maintenance and logistical management. Upon his honorable discharge in 1919, he returned to Washington before moving east to Missoula, Montana, where he secured a permanent position with the Northern Pacific Railway.

Northern Pacific Railway

David’s career with the Northern Pacific Railway spanned over forty years. He was employed as a lead clerk in the Missoula freight depot, a position that placed him at the center of the region's shipping logistics. His primary responsibilities included the meticulous documentation of freight manifests, the scheduling of local rail traffic, and the management of payroll for the yard workers.

His workspace was defined by a strict adherence to protocol. David managed large-scale ledgers that tracked the movement of timber, minerals, and agricultural goods across the Bitterroot Valley. He maintained these records with high accuracy, often working late into the evening to ensure that the day’s transactions were reconciled. Colleagues noted that his ledgers were devoid of corrections or erasures; he viewed the precision of data as the essential component of a functioning railway. He argued that a single error in a manifest could lead to significant delays or financial losses, and he held himself and his subordinates to a standard of absolute technical correctness.

Family Life and the Missoula Home

In 1925, David married Mary Elizabeth O’Shea, a woman from a similar Irish-Catholic background who shared his value for education. They established a home in Missoula, where they raised four daughters. Margaret Ann, the eldest, was born in 1928.

The Sullivan household was managed with the same level of organization David applied to the rail yard. He implemented a structured daily routine that focused on academic achievement and domestic responsibility. Despite the economic pressures of the Great Depression in the 1930s, David maintained steady employment with the railroad, which provided the family with relative financial security. He used his income to build a comprehensive home library, emphasizing the practical and intellectual utility of books.

David was a man of disciplined habits. Every evening after dinner, he presided over a period of study and reading. He required his daughters to read aloud from various texts—ranging from classic literature to technical journals—to ensure they developed clear articulation and an understanding of complex sentence structures. He did not view these sessions as leisure; he viewed them as essential training in communication and logic. He taught his children that a well-constructed argument or a clearly written report was a tool for professional advancement and personal clarity.

Later Years and Retirement

David continued to work for the Northern Pacific Railway through the transition from steam to diesel locomotives in the 1940s and 50s. He adapted to new logistical technologies with the same methodical approach he had used since the start of his career. He remained a respected figure in the Missoula community, known for his reliability and his commitment to the local Catholic parish, where he served on the finance committee.

He retired in 1963, having seen the railroad industry undergo massive changes. In his retirement, he did not abandon his habits of order. He spent his time organizing his extensive personal records and maintaining his home with mechanical exactitude. He watched his daughter Margaret move to Spokane and marry Robert James Murphy Sr., a man whose mechanical skills David respected, even if the two men shared a preference for silence over casual conversation.

David was a witness to the successes of his grandchildren, including James Robert Murphy, who would go on to work for NASA. David saw the technological leaps of the mid-twentieth century not as miracles, but as the logical result of thousands of individuals applying the same principles of precision and hard work that he had practiced in the Missoula rail yards.

Death and Legacy

David Michael Sullivan died on March 12, 1968, in Missoula, Montana, following a brief illness. He was 69 years old. He was buried in St. Mary’s Cemetery, next to his wife Mary Elizabeth.

His legacy was defined by the professional standards he instilled in his children. He did not leave behind a fortune, but he left a blueprint for a life built on industry and intellectual rigor. His insistence on accuracy and his belief in the power of the structured word shaped the career of his daughter Margaret, who in turn shaped the lives of thousands of students in Spokane.

In the years following his death, the scholarship established by his grandson, the Robert J. and Margaret A. Murphy Engineering Scholarship, served as a tribute to the values David championed. Though his name was associated with the administrative side of the railroad, his commitment to the "mechanical poetry" of a job well done remained a guiding force for the next three generations of his family. He remains a representative figure of a generation that valued the quiet, persistent application of logic to the challenges of a developing nation.